| Abstract |

Thrombosis of the cerebral dural sinuses has been well described in the literature and rarely the dural sinus obstruction can result in unremitting papilledema (benign intracranial hypertension or pseudotumor cerebri) causing blindness. We report a case of a 55-year-old man, who was diagnosed to have superior sagittal sinus thrombosis and developed visual deterioration. The patient did not respond to conservative treatment and a thecoperitoneal shunt was performed. Patient is doing well at one-year follow-up with good outcome.

Keywords: Benign intracranial hypertension, cortical venous thrombosis, superior sagittal sinus thrombosis

| How to cite this article: Agrawal A, Swarnakar N. Cerebral venous thrombosis complicated by intracranial hypertension. Ann Trop Med Public Health 2012;5:268-70 |

| How to cite this URL: Agrawal A, Swarnakar N. Cerebral venous thrombosis complicated by intracranial hypertension. Ann Trop Med Public Health [serial online] 2012 [cited 2020 Aug 11];5:268-70. Available from: https://www.atmph.org/text.asp?2012/5/3/268/98636 |

| Introduction |

Thrombosis of the cerebral dural sinuses has been well described in the literature and can present with diverse symptomatology and neurological findings. [1],[2],[3] It has been most commonly associated with sepsis, trauma, pregnancy, the puerperium and many other hypercoagulable states. [1],[2],[3],[4],[5] Rarely the obstruction of the dural sinuses produces a clinical syndrome that resembles pseudotumor cerebri, and severe vision loss can be the presenting sign of cranial venous thrombosis. [1],[3] We report this case to emphasize that in spite of advances in diagnostic radiological techniques, it remains an under-recognized condition and because chronic papilledema may cause progressive visual loss, benign intracranial hypertension (BIH) should not be considered as a benign condition and fundal changes and visual function should carefully be monitored. [1],[2],[3],[4],[5]

| Case Report |

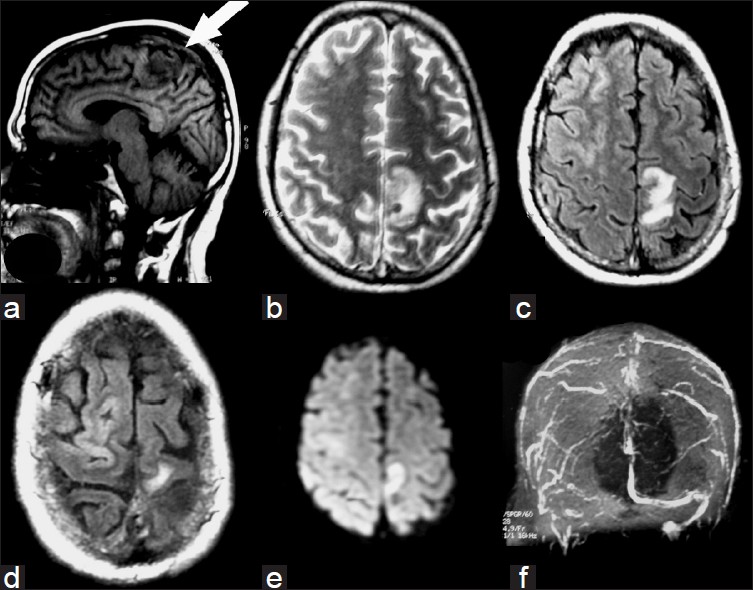

A 55-year-old man was admitted at a peripheral hospital with complaints of sudden onset of weakness of right upper and lower limbs and deviation of angle of mouth to left side of one day duration. There was no history of fever or trauma. He was a known hypertensive on regular treatment but there was no history of diabetes. His general and systemic examination was normal except high blood pressure (170/100 mmHg). On examination he was opening eyes spontaneously, obeying command but confused. Pupils were bilaterally equal and reacting to light. He had right-sided upper motor neuron type of facial nerve weakness. There was grade 1-2/5 hemiplegia involving right upper and lower limbs. Left side power was apparently normal. Deep tendon reflexes were exaggerated on right side and normal on left side. Right plantar was extensor and left was flexor. There were no meningeal signs. With all these findings a diagnosis of cerebrovascular accident was made. He was investigated with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and it showed hemorrhagic venous infarct and associated superior sagittal sinus thrombosis [Figure 1]. The patient was managed conservatively with anticoagulants and gradually improved in his motor power. About two weeks later he noticed deterioration in vision in his right eye. The fundus showed bilateral papilledema. In the right eye he could perceive only finger movements at one foot; however, the vision in the left eye was normal. There was afferent papillary defect in right eye. Repeat computerized scan (CT scan) was apparently normal [Figure 2]. Detailed blood investigations showed hemoglobin 8.8 gm%, total leukocyte count 11.000 (polymorphs 78%, lymphocytes 21% and monocytes 1%). Biochemical investigations were normal. Tests for serum anticardiolipin antibodies and lupus anticoagulant were negative. The patient underwent lumbar puncture study; opening CSF pressure was 24 cm of water. CSF was drained and soon after the patient noticed improvement in his vision. CSF analysis showed normal study. Coagulation profile showed prothrombin time (control/patient 11.6/17.9) with an INR 1.58. The patient was started on oral steroids and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. However he did not respond to conservative management and a thecoperitoneal shunt was performed following which his vision started improving and he is doing well at one-year follow-up.

|

Figure 1: MRI brain showing the evidence of hemorrhagic venous infarct (a-e) with evidence of superior sagittal sinus occlusion (f) |

| Figure 2: (a-d) Follow-up CT scan showing resolution of the clot but mild cerebral edema

Click here to view |

| Discussion |

BIH is a syndrome characterized by elevated intracranial pressure without clinical or radiological evidence of a mass or ventricular enlargement and with normal CSF findings. [5] Although many risk factors including hypercoagulable state or venous stasis (such as oral contraceptives, pregnancy or post-partum period, trauma, prolonged immobilization) have been identified; [6] however, intracranial venous sinus thrombosis leading to benign intracranial hypertension is uncommon. [1],[2],[3],[4],[5],[6] The clinical signs in cases of superior sagittal sinus thrombosis include headache,

focal neurological deficits, seizures and mental disturbances. [7] The most frequent presenting symptoms of BIH include headaches, vomiting and visual disturbances with normal neurological examination (except papilledema and the occasional sixth nerve palsy). [8],[9] If there is development of BIH then additional sign and symptoms of BIH can get superimposed, [7] and severe vision loss can be the presenting sign of cranial venous thrombosis. [3] The diagnosis of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis rests on radiological imaging of the cerebral venous system. [5],[10] These investigations either alone or in combination will confirm the diagnosis of venous sinus thrombosis and at the same time will rule out the hydrocephalus or a space occupying lesion. [10] Angiography has been shown to be the best diagnostic tool and should not be delayed if there is a clinical suspicion of thrombosis. [7] Recently, MR imaging combined with MR venography has been recognized as a safe and noninvasive technique for the diagnosis of venous sinus thrombosis and also for the follow-up. [3],[5],[11] The treatment superior sinus thrombosis associated BIH is controversial and from anticoagulation or thrombolysis to supportive therapy only. [5] If the patient is clinically stable and responds well he/she can be managed conservatively. [5] The conservative management of BIH includes digitoxin, acetazolamide, furosemide and/or corticosteroids. [9],[12] Lack of immediate improvement is an indication for optic nerve sheath decompression, [1],[3],[12] which can subsequently be operated with implantation of a lumboperitoneal, cisternoatrial or cisternoperitoneal shunt. [9]

| References |

| 1. | Horton JC, Seiff SR, Pitts LH, Weinstein PR, Rosenblum ML, Hoyt WF. Decompression of the optic nerve sheath for vision-threatening papilledema caused by dural sinus occlusion. Neurosurgery 1992;31:203-11. |

| 2. | McDonnell GV, Patterson VH, McKinstry S. Cerebral venous thrombosis occurring during an ectopic pregnancy and complicated by intracranial hypertension. Br J Clin Pract 1997;51:194-7. |

| 3. | Cunha LP, Gonçalves AC, Moura FC, Monteiro ML. Severe bilateral visual loss as the presenting sign of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: Case report [Article in Portuguese]. Arq Bras Oftalmol 2005;68:533-7. |

| 4. | Orcutt JC, Page NG, Sanders MD. Factors affecting visual loss in benign intracranial hypertension. Ophthalmology 1984;91:1303-12. |

| 5. | Couban S, Maxner CE. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis presenting as idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Can Med Assoc J 1991;145:657. |

| 6. | Gates PC, Barnett HJ. Venous disease: Cortical veins and sinuses. In: Barnett HJ, Mohr JP, Stein BM, et al, editors. Stroke: Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management, Baltimore, MD: Churchill; 1986. p. 731-43. |

| 7. | Thron A, Wessel K, Linden D, Schroth G, Dichgans J. Superior sagittal sinus thrombosis: Neuroradiological evaluation and clinical findings. J Neurol 1986;233:283-8. |

| 8. | Wraige E, Chandler C, Poh KR. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: Is papilloedema inevitable? Arch Dis Child 2002;87:223-4. |

| 9. | Lundar T, Nornes H. Pseudotumour cerebri-neurosurgical considerations. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 1990;51:366-8. |

| 10. | Higgins JN, Cousins C, Owler BK, Sarkies N, Pickard JD. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: 12 cases treated by venous sinus stenting. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003;74:1662-6. |

| 11. | Ozsvath RR, Casey SO, Lustrin ES, Alberico RA, Hassankhani H, Patel M. Cerebral venography: Comparison of CT and MR projection venography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1997;169:1699-707. |

| 12. | Liu GT, Glaser JS, Schatz NJ. High-dose methylprednisolone and acetazolamide for visual loss in pseudotumor cerebri. Am J Ophthalmol 1994;118:88-96. |

Source of Support: None, Conflict of Interest: None

| Check |

DOI: 10.4103/1755-6783.98636

| Figures |

[Figure 1], [Figure 2]