Background: Pakistan is one of the most populated countries with a population of 160 million; 67% are rural population but all the tertiary care facilities are concentrated in large cities. The Northern Areas is the most remote region with difficult terrain, harsh weather conditions and the tertiary care hospital at a distance of 600 km with traveling time of 16 h. The Aga Khan Medical Centre, Singul (AKMCS) is a secondary healthcare facility in Ghizer district with a population of 132,000. AKMCS was established in 1992 to provide emergency and common elective surgical care. It has strengthened the primary health service through training, education and referral mechanism. It also provided an opportunity for family physicians to be trained in common surgical operations with special emphasis on emergency obstetric care. In addition it offers elective rotations for the residents and medical students to see the spectrum of diseases and to understand the concept of optimal care with limited resources. Methods and Results: The clinical data was collected prospectively using international classification of diseases ICD -9 coding and the database was developed on a desktop computer. Information about the operative procedures and outcome was separately collected on an Excel worksheet. The data from January 1998 to December 2001 were retrieved and descriptive analysis was done on epi info-6. Thirty-one thousand seven hundred and eighty-two patients were seen during this period, 53% were medical, 24% surgical, 16% obstetric and 7% with psychiatric illness. Out of 1990 surgical operations 32% were general surgery, 31% orthopedic, 21% pediatric, 12% obstetric and 4% urological cases; 42% of operations were done under general anesthesia, 22% spinal, 9% intravenous (IV) ketamine, 6% IV sedation and 21% under local anesthesia. Six hundred and sixty-two were done in the main operation room including general surgery 337, obstetric 132, urological 67, pediatric 66 and orthopedic 66 cases; 64% of cases in the main operation room were done under general and 22% under spinal anesthesia. The commonest surgeries were exploratory laparotomy, caesarian sections, open prostatectomy, urological stone surgeries, appendectomy, hernia repairs and surgery for osteomyelitis. There were 21 surgical mortalities including six operative deaths, 15 non-operative deaths and 89% of the mortalities were unavoidable. The crude in-hospital mortality decreased significantly from 5.5% in 1992 to 1.1% in 2001 and the contributing factors were improved structure and process of care. Conclusion: The impact of a secondary care rural medical centre (AKMC) is very obvious from the clinical audit including accessibility, sustainability and quality of care. This could be a model of care in rural Pakistan where accessibility, affordability and quality of care is lacking. Keywords: Rural health, rural Pakistan, rural surgery

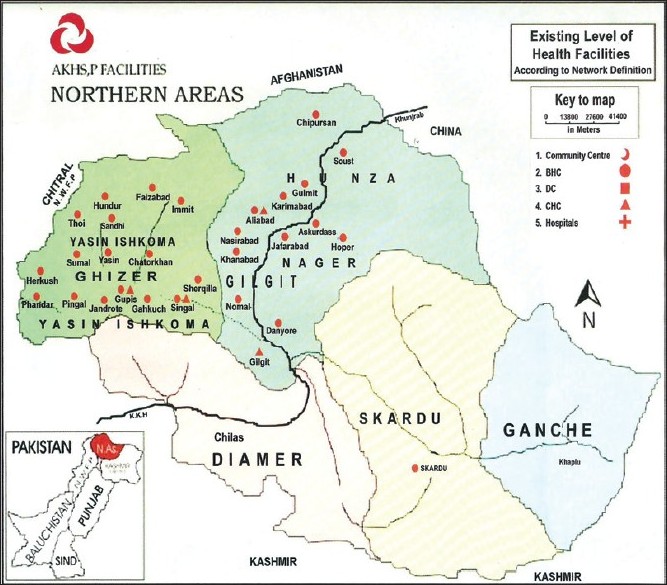

The Northern Areas, officially referred to by the government of Pakistan as the Federally Administered Northern Areas (FANA), is the northernmost political entity within the Pakistani-controlled part of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir. It borders Pakistan to the west, Afghanistan to the north, China to the northeast, the Pakistani-controlled state of Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) to the south, and the present-day Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir to the southeast [Figure 1]. The population of 1,500,000 (2003 estimate), and area of 72496 sq km is divided into six districts in two divisions: the two Baltistan districts of Skardu and Ghanche, and the four Gilgit districts of Gilgit, Ghizer, Diamer, and Astore. There are three district headquarter hospitals in Gilgit, Skardu and Chilas. These are secondary care hospitals where there are facilities to manage common emergency and elective surgical problems including general, orthopedic, gynecological and obstetric and pediatric surgery. The nearest tertiary care hospitals are in Islamabad at a distance of 600 km and a travel time of 16 h through the Karakorum highway, and no air transport facilities are available. The Aga Khan Health Service, Pakistan (AKHS, P) is the largest non-governmental organization (NGO) in the health sector established in 1924. Today, while maintaining that early focus on maternal and child health, AKHS, P also offers services that range from primary healthcare to diagnostic services and curative care. As the largest not-for-profit private healthcare system in Pakistan, its goal is to supplement the Government’s efforts in healthcare provision, especially in the areas of maternal and child health and primary healthcare. AKHS, P operates in the rural areas of Pakistan where it has been reaching people in remote areas with primary and secondary healthcare services since 1974. Today AKHS, P operates 35 health centers, two family health Medical centers and two secondary care hospitals in Gilgit and Ghizer district.

Ghizer district is the northernmost part of FANA with a population of 1500,000 (2003 estimate) spread over an area of 9,636 sq km. There are four administrative units (Thesil) Punial, Gupis, Ishkioman and Yasin with the capital town Ghakuch. All the units are connected through non-metal road with traveling time of 2 to 6 h to the Aga Khan Medical Centre, Singul (AKMCS) [Figure 2].

There are four government rural hospitals in the district but no facilities for in-patient care. AkHSP has been active in this region since 1974 and have a very comprehensive primary healthcare (PHC) system with a network of 16 health centers and two family healthcare units. A population-based cross-sectional survey was conducted in this region in 1995 [1] to assess the burden of acute surgical disease, intervention and outcome. The incidence rates were 1531/100,000 persons per year for injuries, 1364/100,000 for acute abdomen and 16462/100,000 for maternal morbidity. The overall rate of surgical intervention were 411/100.000 of which 11.8/100.000 were operative delivery. The mortality was 55/100,000-this is considered to be a benchmark study to measure the future care of acute surgical emergencies in this district. In Pakistan the rural communities constitute 67% of the population [27] but do not have adequate access to acute surgical care. [3],[4] In 1983 a cross-sectional study of the rural population was conducted [3] and the result revealed that the surgical care was not adequate in 12 rural districts of Pakistan. The overall rate of surgery was 124 per 100,000 persons per year. By comparison the rate of surgery in the United States is 8,253 per 100,000 population. This is a landmark study to be used as a yardstick to measure the state of surgical care in Pakistan beyond the frontiers of megacities where all the private and government tertiary care facilities are concentrated. [4]

Setting AKMCS is a secondary care health facility in the Punial valley of Ghizer district. It has 30-bed inpatient facilities with a major and minor operation room. The medical staff consists of a qualified general surgeon, anesthetist, family physician along with family medicine and surgery residents on rural rotations. The diagnostic laboratory and radiology services are adequate to support the services. AKMCS is the first health facility in Northern Areas to have computerized medical records, pharmacy and financial system. AKHSP is the largest NGO and operates the unit on no profit and no loss basis. The total operational cost was $ 2, 25,580 and 65% was generated through fee for services-consultation fee $ 2, inpatient charges $ 5 per day, and surgery charges $ 25 to 150. Source of data There was a prospective entry of data on software Epi-Info Version 6 using ICD-9 coding system. There was a separate data-gathering system on Microsoft Excel sheet for the surgical procedures and the outcome of surgery including morbidity and mortalities. The unit was generating monthly reports and annual report about the clinical, academic activities, management information and financial indicators. Besides clinical care the general surgeon had the responsibility of general and financial management. There is a medical record system in place and retrievable for review. The descriptive analysis of data was done on Epi-Info-6 about the spectrum of disease, specialty, inpatient census, information about the surgical procedure conducted in the minor and major operation rooms, the information about obstetric patients including prenatal visits, delivery and cesarean section. The morbidity data was analyzed and divided into unavoidable and avoidable deaths. The information about the referral to and from AKMCS was also analyzed.

A total of 31782 patients were seen during the audit period from January 1998 to 2001 at AKMCS with 8029 (25.26%) inpatient admission. Fifty-three percent of the patients had medical disease, 24% surgical, 16% obstetric and 7% psychiatric illnesses. When we look at the geographic distribution 68% were from Punial and the remaining patients from other units (Tehsils) and 3% from outside Ghizer valley. The most common major general surgery procedures were exploratory laparotomy for intestinal obstruction, peritonitis, appendectomy, cholecystectomy and hernia repair. Most of the orthopedic surgeries were performed in the minor operation room for long bone fractures. The comments paed-surgery procedures were done in minor and the major surgeries were exploratory laparotomy, hernia repair and burn surgery. The common obstetric surgeries were caesarian section, dilatation and curettage. The major surgery for urological cases was open prostatectomy and surgery for stone disease. [Table 1] shows an interesting spectrum of procedures done for various sub-specialties of cases. Ninety percent of orthopedic procedures were for long bone fractures in the minor operation room where pain reduction and palter were applied under IV sedation or spinal anesthesia. Again, 93.4% of pediatric surgery procedures were minor in nature including soft tissue infection, soft tissue injuries and circumcisions. Forty-five percent of general surgery and 100% of obstetric procedures were done in the main operation room under general and spinal anesthesia. The obstetric procedures done in the labor room are not included including forceps delivery, vacuum delivery, episiotomy and manual evacuation of retained placenta.

Surgical injuries were one of the common presentations (36%) of all surgical procedures. Most were minor in nature including long bone fractures and soft tissue injuries and were treated in the minor operation room under general IV sedation, spinal or local anesthesia. There were 56 patients with head and spinal injuries, they were treated conservatively or referred to tertiary care hospitals. Agriculture injuries including hand injuries, joint dislocations and soft tissue trauma were common problems of this community Two hundred and eighty-six (14.3%) of the surgeries were performed for acute non-traumatic emergencies and the most common procedure was exploratory laparotomy for intestinal obstruction and peritonitis. The most common cause of bowel obstruction in adults was volvulus and in the pediatric population it was worm infestation. All the emergencies required general or spinal anesthesia. 7.7% of patients required cesarean delivery for obstructed labor, cephalopelvic disproportion, fetal distress or other reasons. Only four patients underwent emergency hysterectomy. There were four in-hospital maternal mortalities including one patient dead on arrival, one with ruptured uterus at the time of arrival and in irreversible shock, the third patient was admitted with prolonged labor, intrauterine death of fetus and sepsis, and the fourth patient died after emergency hysterectomy of postpartum hemorrhage. [Table 1],[Table 2],[Table 3],[Table 4],[Table 5] is summary of the results of the study. In 1986 a baseline study was jointly conducted by Aga Khan Health Service Northern Areas and Aga Khan University Hospital in Ghizer district and the subsequent follow-up by AKHSP and the government health department have verified a significant improvement in health indicators in the Ghizer district.

Pakistan is a densely populated developing country with a population of approximately 160 million; 67% live in rural areas and 21.6% are women in the reproductive age. The crude birth rate is 30 per 100 and maternal mortality rate 500 per 100,000. [22],[23],[34] The rural communities do not have access to the minimal quality surgical care and cannot afford it either. [1],[3],[4] On paper the state has a system in place including basic health units (5171) and maternal and child centres (852) to provide primary healthcare services. Rural health units (551) are supposed to provide secondary health facilities including emergency surgical and obstetric care but unfortunately there is a very unreliable mechanism of implementation and monitoring system. [2],[4],[34] In 1983 a survey of 19 districts of Pakistan was conducted to assess the healthcare system in the rural areas including infrastructure, spectrum of surgeries and the number of qualified surgeons. The study showed an overall rate of surgery of 124 per 100,000 population and the commonest surgeries were gastrointestinal (38%), obstetric (30%), orthopedic (13%) and urological (19%). [2] When we look at the case mix at AKMCS it is in some contrast with the other districts of Pakistan-37% were general surgeries, 30% orthopedic, 21% pediatric, 6.7% obstetric and 4.1% urological surgeries. Orthopedic trauma seems to be a major contributor to trauma and this is probably because of geographic conditions like mountainous region and exposure to agriculture injuries. Injuries were the most common presentation comprising 36% (n=715) of all surgical interventions. Most of the injuries were minor in nature including closed long bone fractures (n=429) and soft tissue injuries (n=210) and were managed in the minor operation room. The major surgical injuries were gunshot, blunt trauma, hand injuries, compound fractures and joint dislocation and required intervention in the major operation room under general or spinal anesthesia. There were 216 emergency surgeries per 100,000 population including orthopedic trauma 77, abdominal emergencies 54 and obstetric emergency surgeries 25 per 100,000 population. The trauma-related mortalities were eight, including poly-trauma, head injuries and gunshot abdomen. Most of the deaths could have been avoided if tertiary healthcare facilities were available in Northern Areas and four of the patients with head trauma were incubated and shifted by road to Islamabad 600 km from AKMCS. According to a national survey the overall annual incidence of unintentional injuries was 45.5 per 1000 per year and an estimated 6.16 million suffered from unintentional injuries in Pakistan annually. [6] But the new wave of terrorism is changing the spectrum of trauma in this country and in an unpublished report, over 40,000 injuries were admitted in four tertiary care hospitals in Karachi over four years and most of them were penetrating injuries including gunshot and bomb blast. The trauma care system none exists in Pakistan but the state is in the process of developing a comprehensive disaster plan and trauma care system in megacities and even at this stage there is no thinking about the trauma care system for the neglected rural communities. A community-based survey of 118 villages was conducted in Ghizer district to estimate the prevalence of surgical emergencies and outcome related to acute surgical diseases which showed 138 injuries per 1000,000 population including burn, fall and road traffic accidents and 123 acute abdomen per 100,000. The report is quite alarming that the injuries related mortalities were 55 per 100,000 and acute abdomen of 53 per 100.000. The mortalities were contributed non accessibility and affordability but there is quite a degree of error or limitation of the survey because the surveyor depended on the skill of the interviewer as happens in verbal autopsies. In this study non-trauma acute emergencies were 286 which comprised 54 surgeries per 100,000 population and the commonest operations were exploratory laparotomy, appendectomy and the other procedures were cholecystectomy, surgery for urological stone and surgery for acute osteomyelitis and septic arthritis. The survey from another rural population of Pakistan showed appendectomy 7, fracture 7 and bladder stones 6 per 100,000 population. [3] In Pakistan the District Hospitals are the focus of secondary surgical care and the variations in different districts could be because of differences in case mix, facilities available and the expertise of the surgeon. Since the overall rate of emergency surgeries were low as per international standards like appendectomy in developed countries are high 138-150 per 100,000 population and same is surgery for groin hernia repair 141 -186 per 100,000 population [1],[3] One of the most important objectives of AKMCS was to provide referral facilities to the entire population of Ghizer district including 16 health centers in 118 villages and four Government hospitals. As there is no other facility in the district to provide emergency obstetric care, the obstetric emergencies were referred to AKMCS. Thirty-one thousand seven hundred and eighty-two patients attended from 1997 to 2001; 12712 were surgical and obstetrics patients and 40% were obstetric cases (n=5085). A total of 132 surgeries were done for obstetric emergencies including cesarean section 74, dilatation and curettage 51, hysterectomy 4 and others 3. The cesarean section rate was 7.7% of 954 deliveries. The cesarean section rate was 14 per 100,000 population and the calculation was based on the crude birth rate of 27 per 100 population. There were no mortality related with obstetric surgeries but there were four maternal mortalities during this period and the underlying causes were ruptured uterus, prolonged labor with sepsis, and one patient died after hysterectomy for postpartum hemorrhage. The national cesarean rate in the rural population is reported as very low, 0.51%, and only 9.1% of the pregnant females have accessibility to emergency obstetric care. [34] In another study the overall cesarean rate in Pakistan’s rural population was 9 per 100,1000 and in the developed countries the rate is 236 per 100,000 population. The rate of cesarean section is variable in developing and developed countries. In urban Pakistan it has been reported between 13-20% and interestingly 80% were emergency surgeries. [25],[26],[27] In developed countries the cesarean section rate is varied between 18-27%. In one prospective study the cesarean rate decreased from 17% to 11% by following a protocol and without increase in peri-natal morbidities. According to United Nations’ (UN) recommendations, there should be at least one comprehensive and four basic emergency obstetrics care facilities per 500,000 population and in a survey to meet the UN’s minimum standards for the population of rural Pakistan was conducted in 2004 and the results showed poor state of obstetric care in rural Pakistan, only 9.1% pregnant females has accessibility to obstetric emergency care and the cesarean section rate were far below (0.05%) the UN recommendations (5-15%). [Table 6] shows the impact indicators of AKMCS on the population of Ghizer district with an estimated population of 132000. A baseline survey was conducted in 1986 which revealed a very poor state of health with maternal mortality of 550 per 100,000 and infant mortality of 158 per 1000 births and in 2001 the maternal mortality decreased to 130 per 100,000 and infant mortality to 44 per 1000 live births. If we look at Pakistan’s national figures the basic health indicators are not encouraging with MMR of 500 per 100,000 population and IMR of 80 per 1000 live births. [22],[23]

Maternal mortality is perhaps unique among public health problems in that its reduction depends on treatment rather than on prevention. This concept is further validated by this study that primary healthcare though started in this district in 1978 the real reduction in maternal and infant mortality was achieved by establishing secondary surgical facility (AKMCS) in Ghizer district. The second important question is the result of cesarean delivery by the general surgeon and trained family physician as in this study there was no mortality related with cesarean section and this is also supported by others. [12] In Ghizer district there is one general surgeon, family physician and anesthetist for the entire population and no pathologist, radiologist and internist in the entire district. Relatively few trained surgeons were available to the rural population of Pakistan because of no financial or academic incentives for the rural surgeons, poor infrastructure, communication and no opportunities for continuing medical education. The Aga Khan University Hospital in Karachi has a very comprehensive and broad-based residency program in general surgery and family medicine and the young graduates are the future assets to develop rural health facilities in Pakistan but the state should have to change their priorities to provide minimal standard of surgical care as defined by the UN to improve on the basic surgical care for the poor rural population.

Developing rural surgical care is a challenging task for a country like Pakistan where 67% of the population is rural and so far it has not achieved the UN goal of health for all by the year 2000. Aga Khan Medical Centre, Singul achieved the desired objective and results with limited resources and budgetary provision. This model could be replicated in other rural areas of the country to provide accessible, affordable and standard surgical services.

I am grateful to Professor Mushtaq Ahmed and Dr. Imam Yar Baig for their advice and encouragement. I also acknowledge the efforts of Dr. Khalid Choudry who developed safe anesthesia service in this remote region. Here I also acknowledge the support of family physicians Dr. Israr Khan, Dr. Mohd Karim, Dr. Nisar and Dr. Ghari Khan. [36]

Source of Support: None, Conflict of Interest: None

[Figure 1], [Figure 2]

[Table 1], [Table 2], [Table 3], [Table 4], [Table 5], [Table 6] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||