Introduction: The birth of a malformed infant and hospitalization in the Intensive Care Unit will create different psychological effects in the mother and while increasing the level of anxiety will affect important psychological processes such as attachment. On the other hand, the implementation of support programs and providing the required information and training to mothers make them feel more in charge and have more power over their positions. Objective: The objective of this study is to determine the effect of the support program on the attachment of mothers of infants with gastrointestinal abnormalities. Methodology: The study is a randomized controlled clinical trial that was conducted after the verification of the Ethics Committee (approved on November 9, 2014, with the ethics code of 5/4/7621) of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences and registering in Iran Clinical Trial Center (IRCT201409264617N10). Moreover, the study was conducted in neonatal ward of children’s Hospital of Tabriz/Iran from late October 2015 to mid-May 2016 on 50 women with abnormal infants. This study is a randomized controlled clinical trial. Fifty mothers, who met the conditions of inclusion in the study, were randomly placed in two groups of intervention and control, and maternal attachment was examined using Korean test. In the intervention group, support program was conducted in two aspects: psychological support by clinical psychologist and caring by researcher, each in two sessions of 45 min. After obtaining the posttest from both groups, the data obtained were compared using the statistical test of comparing means and Chi-square test. Results: Some demographic characteristics of mothers (such as level of education, age, occupation, number of children, financial support resources, and baby’s gender) showed no significant differences in the two groups using the Chi-square test. Comparing attachment changes in the two groups after the implementation of the support program showed that the rate of changes in the intervention group was more than the control group (P < 0.05). Conclusion: This study showed that the implementation of the support program is effective in the attachment of mothers of infants with gastrointestinal abnormalities. Thus, creating and developing support programs by nurses to empower these mothers in taking care of infant and the efforts to promote attachment between mother and infant in hospitals seem essential. Keywords: Attachment, digestive disorder, support program

Congenital malformations are of the causes of the spread of diseases, mortality, and long-term disability in childhood and later on.[1] They exist at birth and are divided into structural, functional, metabolic, and hereditary groups.[2] Congenital malformations are reported to be the cause of hospitalization of one-third of the infants in hospitals. Physical examinations have shown that about 2%–3% of babies have structural defects that lead to disability or premature death later.[3] According to the World Health Organization report, about three million babies are born with abnormalities each year accounting for 2%–3% of all live births.[4] Statistics showed that 3% of babies in the UK, 2% in Turkey, and 1.49% in South Africa are born with congenital abnormalities.[5] Studies conducted in Iran show that the prevalence of abnormalities is different in different cities. Shajari et al. (2001–2004) reported the prevalence of abnormalities in Tehran as 3.1%[6] and 2.4% in Sizvar, the most common of which are related to musculoskeletal and then urinary-genital system.[7] In Ardebil, the prevalence has been reported 8.2 cases/1000 live births where the highest abnormality is related to musculoskeletal system and the lowest to chromosomal abnormalities.[8] Statistics are not available on the prevalence of abnormalities in Tabriz. Attachment can be considered as a warm, sincere, and lasting relationship between mother and baby satisfactory to both which facilitates the communication and interaction between mother and baby. Attachment is a pattern that has been associated with humans and is constantly changing and evolving.[9] This relationship is created from the beginning of pregnancy and gradually increases, so that in the third trimester, it reaches its peak and promoted after delivery through mother and baby eye contact, smell, and touch.[10] The interaction between infant and mother is of great importance in creating attachment.[11] In general, a healthy baby is the best gift of God for a mother and facing a sick infant creates an acute crisis for parents, especially mother.[12] The birth of a malformed infant and hospitalization in the intensive care unit create different psychological effects on mother, and while raising the anxiety level, they affect important psychological processes such as attachment.[13] Birth of a child with physical defects and deformities terminates mental attachment of mother to the ideal child during pregnancy.[14] The birth of an abnormal baby creates exactly the same psychological reactions in the parents as the death of the child.[15] The study by Drotar et al. in America showed that after the birth of an abnormal baby, parents show five stages of shock, denial, sadness, anger, and adaptation.[16] If establishing the communication between mother and baby happens with delay due to infant sickness, it may affect infant development, adoption of parental identity, and harm the mother’s abilities to care for the baby.[17],[18] On the other hand, mother’s attachment behaviors toward the baby play an important role in the acceptance of parental identity, the future relationship between mother and baby, and infant growth and development.[18] Kusseno C, et al. (1998) have noted that the most sensitive time for mother-infant attachment process is 45–60 min after birth.[19] Postpartum attachment behaviors start with actions such as touching the baby with fingertip, touching the organs of the baby, kissing the baby, hugging the baby, talking to the baby, eye contact with the baby, and smelling the baby by the mother.[20] Malformed babies are hospitalized in the hospital Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) from the birth, and the mother may not have the chance to embrace the baby and have contact with it immediately after birth, so mother-infant attachment may be impaired.[21] Currently, there is no purposeful and organized intervention in Iran to support the mothers of malformed infants to reduce the problems mentioned, so it seems that the notification and implementation of training programs for these mothers are of considerable importance. Several studies have shown that supporting the family and giving information and education to them make them have more sense of control and power over their own situations and get a more realistic view of the appearance and condition of the baby so act better and more actively in taking care of the baby.[22] Thus, according to the above-mentioned points and giving the importance of attachment and the lack of comprehensive studies in this regard, this study is done aimed to determine the effect of support program on attachment of mothers of the babies with gastrointestinal malformations.

The study is a randomized controlled clinical trial that was conducted after verification by the Ethics Committee (approved on November 9, 2014, with the ethics code of 5/4/7621) of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences and registering in Iran Clinical Trial Center (IRCT201409264617N10). Moreover, the study was conducted in neonatal ward of children’s Hospital of Tabriz/Iran from late October 2015 to mid-May 2016 on 50 women with abnormal infants. For determining the sample size, given that there was no similar studies done in Iran, a pilot study was performed on ten subjects and considering α = 0.05, power 0.08, difference 0.05 in changes of attachment, and with an estimated 10% probability of sample loss, 25 subjects were considered for each group and 50 as the final sample. The inclusion criteria were a definitive diagnosis of congenital gastrointestinal malformations in the infant, surgery on infants, and a literate mother, and in case of transferring the baby to the intensive care unit, neonatal life-threatening problems, particularly receiving antidepressants by the mother, and the occurrence of major stressful accidents for the mother, they were excluded from the study. The mothers who had the inclusion criteria were selected, and after explaining the objectives and completing the form of informed consent, they were assigned randomly to two experimental and control groups using Rand list software. The instrument used in this study was Koren’s (2007) attachment questionnaire that is a self-report instrument. This questionnaire assesses mother-infant attachment with 26 four-choice questions. The scoring of questions is as 4, always; 3, sometimes; 2, rarely; and 1, never. The range of scores is from 26 to 104 where the score below 65 indicates a low attachment and above 65 represents a high attachment.[23] The reliability of this instrument was calculated in 1994 by Bhakoo with Spearman r = 83%.[23] The reliability in this study was obtained using Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.72) that shows acceptable reliability of the test. On the first day of the study, both groups completed Korean’s attachment questionnaire. Then, the support program for mothers in the intervention group started in a quiet room outside the ward in psychological support by clinical psychologist and care support by the researcher. The first phase which included psychological support by the clinical psychologist and with the presence of the researcher took place individually in two sessions on the second and 4th days after the hospitalization of the baby for 45 min in neonatal ward. During the first session, the psychologist evaluated the information and views of the mothers about the abnormality problem of their babies for 10 min, and then, the mothers were encouraged to express their fears and concerns. Psychological support included the following: (a) Questions about the perceived social support systems by the mother (such as a spouse, family, and friends), (b) training strategies to reduce anxiety according to maternal mental status including, the following (relieving from stress by teaching relaxation and relaxation in action, breathing deep, warm water shower, explanation about the importance of proper nutrition, encouragement to have adequate fluid intake, teaching techniques to increase confidence in the form of educational booklet, and strengthening mothers’ coping methods in the face of anxiety and if needed consultation with spouse to strengthen emotional connection of parents). It should be noted that the above support program was implemented in accordance with the needs of the mother and was quite flexible. In the second session, the first 10 min was in questions and answers format about the extent to which what was said during the first session was effective in reducing anxiety. Then, the importance of mother-infant attachment was talked about. Moreover, given the special status of the babies, training attachment-increasing behaviors including emphasizing the importance of mother’s voice and her vocal pattern in the formation of mother-infant attachment, the mother’s lullaby voice, mother-baby face-to-face contact, stroking the baby and physical touch of the baby and stressing its importance began. The second stage of the support program was done after baby’s digestive surgery, during two 45-min sessions on two consecutive days in the neonatal ward individually by the researcher. During the first session, by asking a few open-ended questions, mothers’ information about abnormalities of their babies and taking care of them were evaluated, and then enough explanations about the anomalies were given in a plain language using images and educational pamphlets available in the ward. In the second session, first, a training manual containing information about the role of the mother in the care of the abnormal baby, the benefits of breastfeeding and the method of breastfeeding, changing nappies, bathing baby, the quality of hugging, massage training and that according to the abnormalities of the babies what care they need after the operation, and how they can establish a constant and effective relations with the baby was given to the research units. All of the above points were trained practically face-to-face. During these two sessions, the researcher stressed on reinforcing the positive and healthy aspects of the infants, and the mothers were encouraged to ask their questions. After the implementation of the support program and at the end of the last training session, once again Korean’s attachment questionnaire was given to research units. Finally, for educational support of the control group after the completion of data collection, the training manual was given to them. The obtained data were analyzed using SPSS 21(Statistical package for social science) statistical software and descriptive and inferential statistics. For comparing the qualitative variables of the two groups, Chi-square test and for comparing quantitative variables, independent t-test and paired t-test were used. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in this study. Multivariate models were used to eliminate the effect of confounding variables.

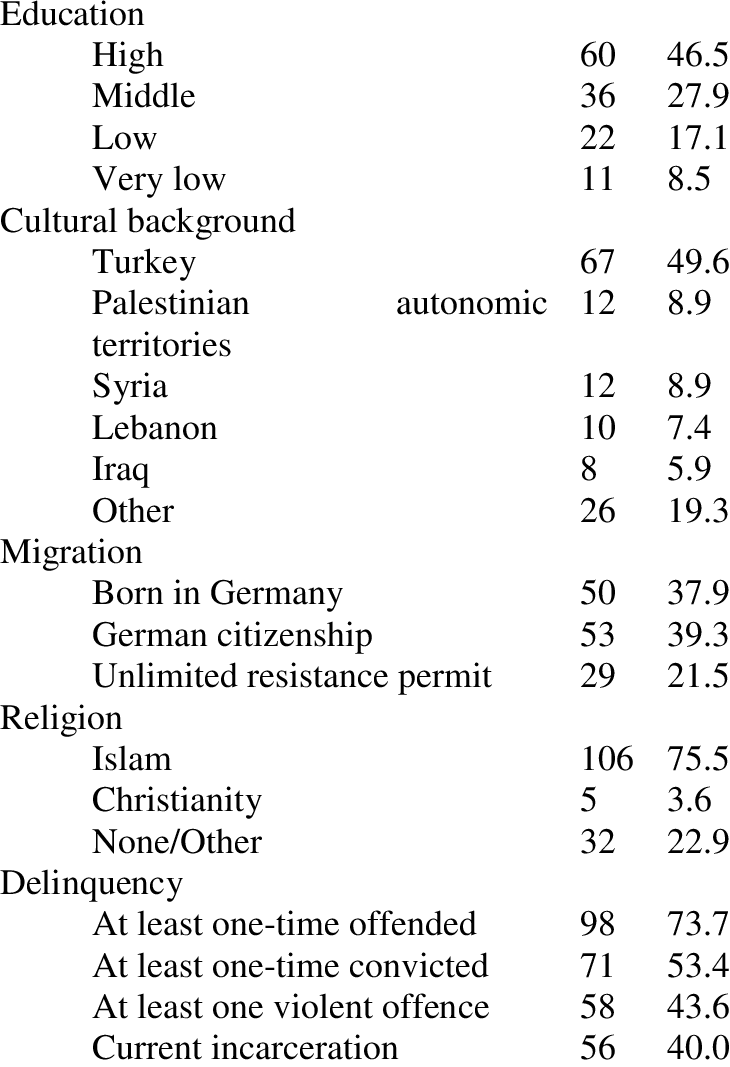

In this study, all mothers continued the study until the end. [Figure 1] Comparing some demographic variables of the mothers in terms of educational level, occupation, number of children, sources of financial support, gender, age, and weight showed that the two groups have no significant differences in terms of the above [Table 1] and [Table 2].

The results showed that the mean maternal attachment in the control group in pre-test was 83/4±92/45 and in post-test was 89/4±00/47. The results of statistical test showed that there is no significant differences in the maternal attachment at the beginning and end of the study (P>0.05). Mean attachment of the mothers in the intervention group in pre-test was 51.88±4.48 and in post-test was 59.32±6.38. The test results showed that there is a statistically significant difference in the maternal attachment at the beginning and end of the study (P<0.01). Independent t-test showed significant differences between the intervention and control groups in attachment changes (P = 0.01) [Table 3].

This study was conducted aimed to determine the effect of support program on attachment of mothers with infants having gastrointestinal abnormalities. According to the findings, maternal attachment scores in the two groups showed no significant differences before and after the implementation of the support program. However, mean attachment scores of mothers in the intervention group increased after the implementation of psychosocial and care support program. This change was minimal in the control group mothers, and this difference was statistically significant. Therefore, the implementation of psychosocial and care support program has been effective in increasing maternal attachment of the mothers having babies with digestive disorders. The results of this study are supported by the following studies. In a study by Abbasi et al. (2009) and Tousi et al. (2010) determined the effect of training attachment behaviors on the attachment of mothers of first delivery. The results showed that training and performing some attachment behaviors increase maternal attachment and enhance the relationship between mother and infant, and improve the development of cognitive, social, and emotional aspects of the infant.[24],[25] The results of Karbandi et al. (2015) showed that the implementation of support programs affects the increase of maternal and premature infants’ attachment behavior.[13] In contrast to these studies, in a study by Weis et al. in Denmark, “guided family-centered care intervention” was used as a stress management intervention for mothers of preterm children hospitalized in NICU. This method was nurse-parent intervention helping parents manage their emotional problems in NICU and improve their power to make decisions about care for their baby. The results showed no significant differences between the intervention group and the standard care group. The researchers stated that the reasons for this result are the insufficient sensitivity of the tools used or design of the study and the possibility of spreading information among nurses in both groups.[26] Several studies suggest that other factors such as the number of deliveries, mother’ previous experiences,[27] participation or nonparticipation of the father in the study, teaching method intervention type,[26] and features of mother and baby [28] affect the expected results. In this regard in a meta-analysis study on the effect of various intervention programs in maternal sensitivity and attachment, Bakermans-Kranenburg et al. reported that interventions in specified issues based on behavior and the average number of sessions have the most effectiveness.[29] In their systematic review, Evans et al. concluded that given the diversity of parental teaching and interventions methods, to improve the quality of the relationship between mother and premature infants, a combination of the existing methods, and simple, feasible procedures should be used in clinical centers.[28] Mothers are the important element in the care of newborns with birth defects. Since attachment leads to behavior changes in mothers including the feeling of fresh power and awareness of the baby’s needs leading to increase in self-confidence and anxiety reduction in its turn, the interested mother looks forward to an opportunity to care for their own children.[30] Finally, attachment leads to improvement in mother-infant relations and increase in the physical and mental health of the baby. Thus, attention to strategies of improving attachment and removing obstacles of the attachment between mother and baby should be considered as an important matter in prenatal care. As was explained in the introduction, the special status of newborns with birth defects and its impact on attachment on the one hand, and more need of these babies for maternal support and her important role in the care and protection of baby on the other hand make the necessity to pay attention to mother-infant attachment more evident in babies with birth defects. As the results of this study and similar studies, the support of mothers to children with abnormalities is effective in increasing their attachment. Therefore, taking into account the importance of family-centered care, changing the parents into active members of caring rather than observers, the good efficacy and relatively inexpensive nature of the protection method used in this study, and its matching with the background and culture of Iran, this method can be used as a prototype to setup counseling and psychological support and care in the NICU units in Iran and countries with similar cultures. Moreover empowering health workers, especially nurses working in neonatal units about supporting parents of babies with abnormalities can be effective in promoting parent-child relationships. On the other hand, considering the probability of identifying some of these birth defects during pregnancy, one can prepare educational and counseling programs for mothers during the prenatal period, so that they are better prepared to face communication and care of such babies. Among the limitations of this study, several factors including cultural, social, economic, and psychological, etc., factors can be cited that can indirectly affect the level of maternal attachment. However, in this study using randomization, it was tried to keep these effects minimized. Moreover, although the incidence of major stress events in the mothers was under control during this study and in case of such incidents, people were excluded from the study because their little stresses of everyday life cannot be controlled this was considered as one of the limitations of this study. In the study, self-report instrument of maternal attachment was used that like other self-report instruments has its limitations. Therefore, it is suggested that in other studies, other tools such as observing maternal behavior be used to determine the attachment. Moreover, it is suggested that a study with a larger sample size be conducted.

This study showed that the implementation of the support program is effective in the attachment of mothers of infants with gastrointestinal abnormalities. Thus, creation and development of support programs by nurses and midwives to empower these mothers in the care of babies and to promote mother-infant attachment in the hospitals seem essential. Acknowledgment This article is a part of a master’s thesis of a student of nursing of NICU conducted in the form of an approved project in Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. Thus, researchers see it necessary to thank and appreciate Tabriz children-hospital authorities’ collaboration, head nurse, neonatal section personnel, and the mothers participating in this test. Moreover, the Deputy of Research and Student Research Center of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences is thanked for his financial support of the project. Financial support and sponsorship Nil. Conflicts of interest There are no conflicts of interest.

Source of Support: None, Conflict of Interest: None

[Figure 1]

[Table 1], [Table 2], [Table 3] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||